“Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel would never have existed if it wasn’t for the composer’s sister, the German folklore enthusiast Adelheid Wette”

The story of Hansel and Gretel begins in 1812 when two academic brothers, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, publish a set of stories entitled Kinder und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). The collection was huge and included the old German tale of Hansel and Gretel. But the opera we know today would never have existed if it wasn’t for the German author, composer, poet and folklore enthusiast Adelheid Wette.

Born in Siegburg, near Bonn, in 1858, Adelheid’s interest in literature and folklore began as a child. In 1881 she married Dr Hermann Wette, himself a keen ‘folklorist’ and part-time librettist. As their family grew, Adelheid began to write short plays for private performances, with her children often involved. In 1888 she wrote a version of the fairy tale Schneewittchen (Snow White). This required some music and so she wrote to her older brother Engelbert requesting that he create musical settings for some of her verses.

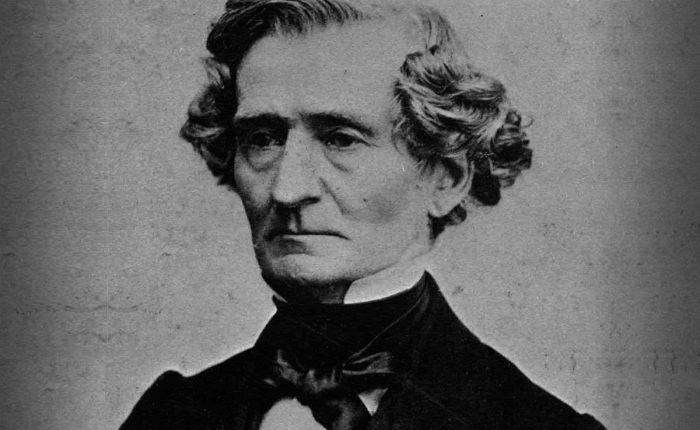

Engelbert Humperdinck had studied music at the Cologne Conservatory and, later, the Royal Music School in Munich. In 1879 he met Richard Wagner who invited him to Bayreuth to assist him in the preparation of his final opera Parsifal. For two years Humperdinck immersed himself in Wagner’s music and Parsifal in particular, allegedly even writing a few bars of the opera!

By the late 1880s Humperdinck was living in Cologne trying to make it as a composer. On receiving his sister’s request, he obliged with settings of eight songs for children’s choir and piano. Further collaborations ensued. And then, at the beginning of 1890, Adelheid began a draft of Hansel and Gretel. Her husband Hermann would be celebrating his 34th birthday on 16th May and Adelheid had hatched a plan to surprise him with a private family performance of her play. With just a month to go she wrote to her brother, with very specific requests: she needed a Tanzlied (dance song), a Waldlied (forest song), a Schlummerlied (lullaby) and a Kickerickilied (cock-a-doodle-doo song)! She enclosed all the verses and even provided rhythms for the dance song and a melody for the lullaby.

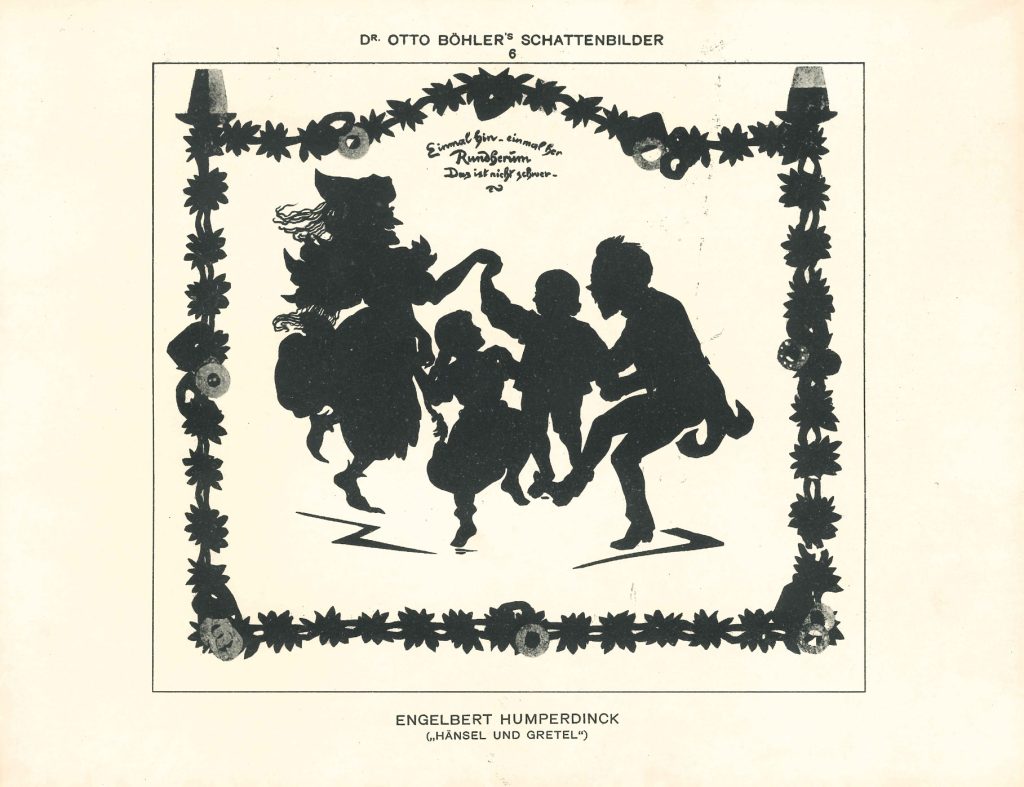

Humperdinck worked fast, incorporating Adelheid’s musical ideas and completing all four songs within a few days. The songs were set for two young voices and piano and were sung by the Wettes’ two eldest daughters in the performance which took place, as planned, for Hermann’s birthday. Such was its success that plans were made to enlarge the work into a singspiel, a German form of music theatre, the most famous of which was The Magic Flute composed almost exactly a century earlier. Adelheid’s husband got stuck in as well, helping with the text, and for Christmas 1890 the new version, complete with numerous musical numbers and dialogues, was performed privately at the Wettes’ house. It was a triumph and Humperdinck was immediately persuaded that the work could be further extended into a fully-fledged opera.

Now living in Frankfurt, Humperdinck was to spend the best part of three years working on the opera. Adelheid provided the text. With her knowledge of fairy tales she filled out the story, skilfully interweaving a number of well-known folksong lyrics and sayings into the work. She added the Sandman and the Dew Fairy, and her empathy for the children proved crucial. So too was her sympathy for the mother and father, so that the audience feel for both parents rather than being set against the mother, and at the end it is the anxious parents who find their beloved children. Her intuition for the stage, in countless points of detail, was critical, and it was Adelheid who provided her brother with the overall framework for the opera.

The first performance took place on 23 December 1893, in Weimar. It was conducted by the composer Richard Strauss, without the overture as the parts hadn’t arrived in time! It was an instant success, captivating audiences and critics alike, and the work spread like wildfire across Europe, reaching London in 1895. It was the first significant German opera since the death of Wagner and proved the perfect antidote to the rapidly emerging works of the Italian verismo school led by Mascagni, Leoncavallo and the young Puccini.

Humperdinck’s opera contains a unique blend of simplicity and complexity. In truth, it’s a bit of a miracle, and shouldn’t have worked at all, for it sets a simple children’s story over a richly orchestrated late romantic score. ‘Wagner meets fairy tale’ doesn’t sound like a marriage made in heaven. Yet somehow the composer was able to remove any sense of incompatibility that might have existed between his lavish orchestration and his innocent little melodies. This achievement turned out to be a one-off, never to be repeated; Humperdinck tried, producing several more stage works right up until his death in 1921, but none of them came close to recapturing his earlier success.

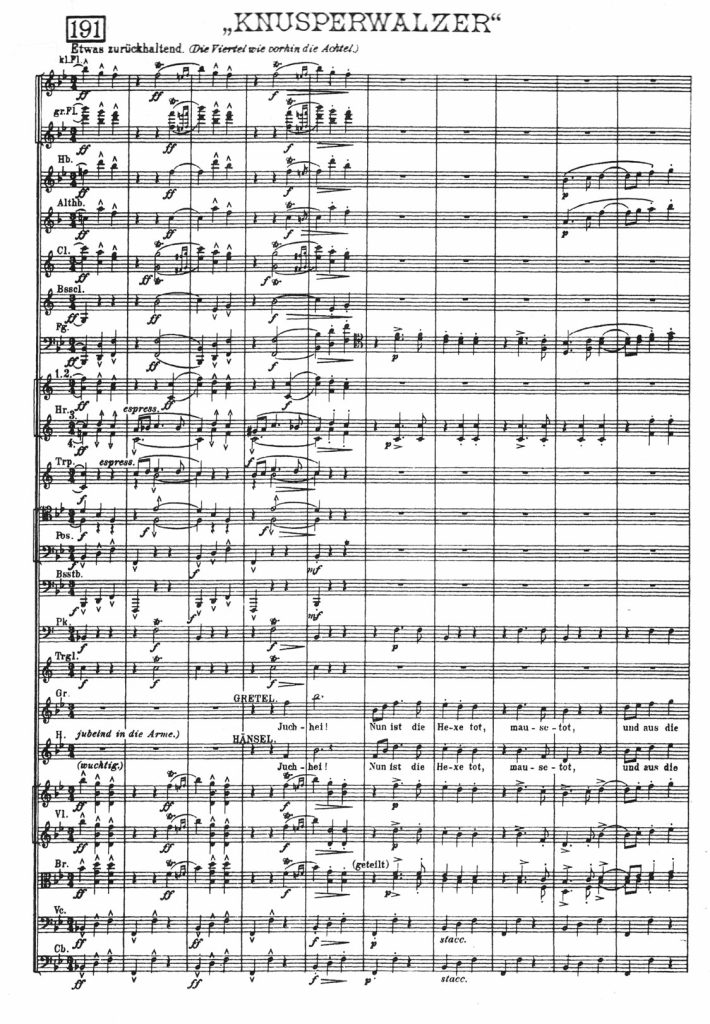

I’ve spent the last twelve months immersed in the score, producing a reduced orchestration for MWO’s new production. In the original, most of the instruments play for most of the time – there is little rest for the players and there have been many days when I’ve spent hours working on just a few bars. The score is fearsomely contrapuntal – that is, for much of the opera the harmonies are created by interweaving instrumental lines, each with melodies locking into each other to create their own harmony. Take an instrument away, and the whole thing collapses, rather like some nightmare version of a children’s game where you’re trying to move one stick or block without the rest falling down.

Yet, throughout, there is a plethora of catchy and engaging music. The childrens’ songs, so tuneful and memorable; the easy domestic opening of Act 1; the atmospheric woodland setting of Act 2 with its cuckoo call and its myriad of birdsong; the magical musical setting of the Sandman; the wonderful and rightly famous hymn at the end of Act 2; the witch’s dance in Act 3 and the Knusperwalzer (crunchy waltz) that Hansel and Gretel dance when the witch is finally dead. For those of a more richly romantic vein, the opera contains lush, high voltage orchestral interludes that separate the scenes. These include the Hexenritt (witch ride) and the Traumpantomime (dream pantomime), both performed on a regular basis in the concert hall.

Hansel and Gretel also contains a fabulous overture, or Vorspiel (Prelude), comprising themes heard later in the opera, a common nineteenth century practise. It opens with the Act 2 ‘hymn’, a melody that recurs during the opera and reaches its zenith at the end of the ‘dream pantomime’. Contrasts ensue, with plenty of flowing melody and lots of high energy. Humperdinck summed it up as ‘Children’s Life’, a very good description. But what really makes the overture is a characteristic to be found throughout the work, giving it its everlasting appeal. It nourishes the soul, like an open fire in your sitting room on a cold winter’s day. Sparks may fly but the overall effect is of comfort. And I can confirm that, unlike with the work’s premiere, the overture will be included in MWO’s first ever performance of this magnificent opera.