by MWO’s Music Director Jonathan Lyness

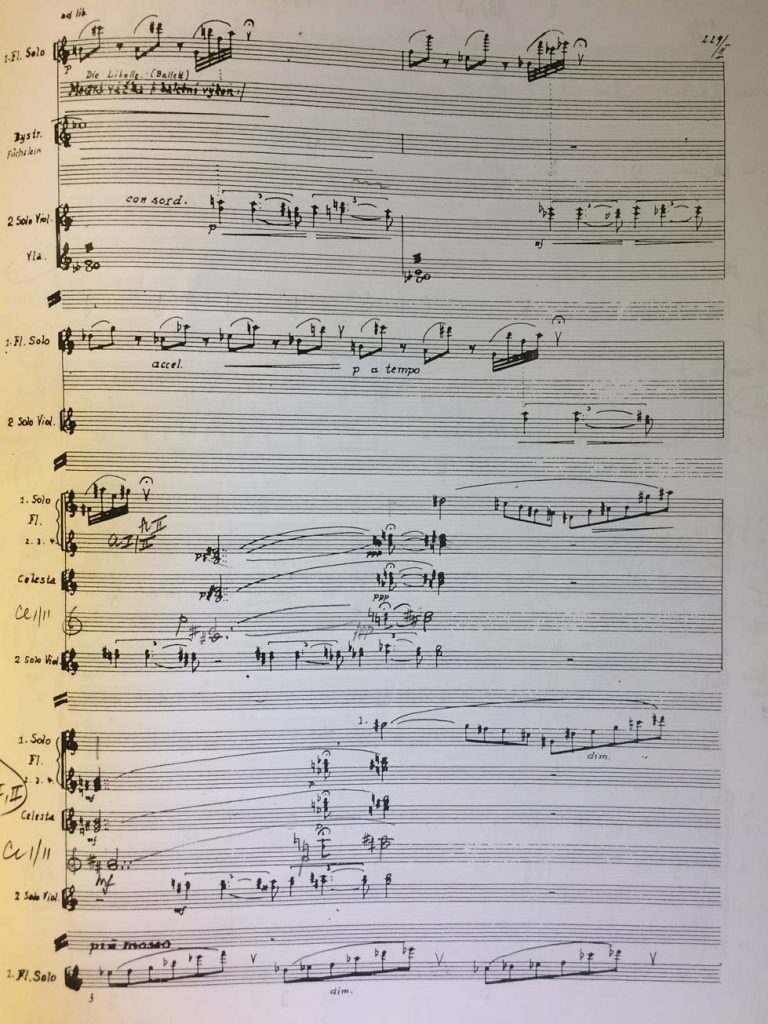

When lockdown arrived in the second half of March, and with our beautiful tour of The Marriage of Figaro tragically cut short, I’d already spent three weeks working on a new reduced orchestration of one of Leoš Janáček’s last great operas The Cunning Little Vixen. I’d conducted the piece in 2008 and then, around five years ago, had started tinkering around with it, encouraged by the idea of performing the opera with a smaller group of players than the large orchestra for which it was composed. In early March I opened up my full score again (1924 edition), which is not always entirely legible, to find it made even more illegible by my pencilled annotations and copious notes (literally) on how the parts could best be divided amongst just thirteen players. And so, there I was, at 7.00am at my home in Lingen, with coffee in hand and score in front of me, switching on my laptop, opening up ‘Sibelius’, and hitting ‘New…’.

At this point, normal procedure is to enter a key signature. But here, as in so many ways, Janáček departs from the norm. The Cunning Little Vixen has no key signatures! It seems such a simple thing, but players generally prefer a key signature rather than multitudes of accidentals. But if there’s one thing string players really don’t like, it’s playing in too many flats. For violinists, this is a particular issue – it means squashing their left hands against the scroll of the instrument, almost into a half position, which is uncomfortable (especially for those with big hands!) and makes vibrato difficult to accomplish. Puccini loved A-flat minor (with seven flats), but he holds nothing on Janáček, who uses many flats, and regularly uses whole sequences of double-flats, often in bars or phrases that also include the odd sharps or even double-sharps. It’s not so much that it’s difficult to play – it’s just difficult to read!

As for time signatures… Well, yes, Janáček does at least give us time signatures. But that’s almost a misnomer and the time signatures are often irregular and exotic, and not necessarily indicative of the pulse of the music. Here’s the thing: Janáček’s music is infused with folk-song elements, with twists and turns often hard to notate, both harmonically and rhythmically. Then there is his obsession with the Czech language, which he endeavours to notate as naturally as possible. And then, in Vixen, he goes one stage further, with his melodic ‘characterisations’ of animal sounds. Here the composer has become a musical naturalist, and there are places in the score where he does actually abandon the time signature altogether, a prime moment being when the vixen and fox disappear off-stage to make out (!). It’s clear to me that much of Janáček’s melodic material appears to him in a natural state, without reference to time or key signature, but with a melodic purity that he subsequently notates as best he can.

That’s all very well, until we find separate phrases that seem as if they should be rhythmically identical, but in fact are different just because of the way they’re notated. Which version to choose?! On a broader level, the fastidiousness towards scene-flow that we see in the operas of Verdi and Puccini (and later, in Britten) does not always appear to be at the forefront of Janáček’s mind. Instead there are countless times where it seems that, as a performer, one is being asked to square a circle. Janáček will mark ‘accel.’ (getting faster) into a section that is steadier, and vice versa. And commonly a rhythmic motif reaches a point where either the motif must dissipate or stagnate in a way that no composer could have desired, or the musical flow must be so abruptly altered that the effect is that of a bad gear change. Someone once told me that the late Charles Mackerras, a pioneering conductor of Janáček, struggled with these issues and, in the end, had simply done his best to work through them, as if dealing with a set of jigsaw pieces that must, occasionally, be cajoled and/or manoeuvred into place.

Janáček wrote The Cunning Little Vixen during the extraordinarily creative period at the end of his life when, in his sixties, he produced many of his greatest masterpieces. Composers at this time (1920s) were still writing what’s called a vocal score – that is, voices with piano accompaniment – and subsequently orchestrating them. Janáček’s method was to compose straight into full score, and his manuscript paper had many, many staves. He would write ‘ideas’ – so, horns here, or clarinets there, or strings on one stave only, divided, say, into four parts and called simply ‘violins’, or ‘violas’. So there might be a passage with violas and double basses divided into many parts, and violins and cellos doing nothing at all. That was clearly the sound he wanted, and he wasn’t going to ‘conform’ to the normalities of string divisions for the logistical benefit of a ‘normal’ orchestra.

In addition, he excels in giving instruments parts that are almost impossible to play. I remember as a student, studying his Piano Sonata 1905, discovering that pianists without the benefit of three hands would invariably have to resign themselves to ‘doing their best’ in an effort to keep rhythms aligned and tempos flowing. In Vixen, in the beautiful transitory night scene in Act 1 leading towards the dawn chorus, the clarinet, marked ‘piano’, sails up to an unbelievably high top B-flat whilst the flute sits close by wondering why he/she isn’t playing, and in the love scene between the vixen and fox, the flute is expected to play repeated high ‘piano’ C-sharps while the piccolo sits twiddling his/her thumbs in the next door chair. The strings are frequently given whole phrases of unobtainable harmonics, and then there’s the harp part! Much of this is quite simply unplayable, meaning that harpists have to decide how to adapt it in certain places to produce something close.

Did Janáček know how a harp works? Of course he did. Janáček simply wrote what he wanted, without the niceties of orchestral filling, seamless continuity, correct spelling or instrumental friendliness. The result is a kaleidoscopic richness of ideas, and it is left to others to make his music work. When Mackerras first discovered Janáček and ‘introduced’ him to the UK in the late forties/early fifties, he was asked to describe the music, and he said “well, it’s a mixture of Mussorgsky and Debussy and Mahler and Sibelius etc… and all these composers kind of wrapped up and I can’t really describe it – we’ll just have to do it and you’ll see!”

Nice! When are the auditions?! 🙂

We’ll let you know!